How do you take a photo of a movie?

First, you need to figure what a movie actually is. What do you point the camera at? You could begin by pointing it at a screen and taking a picture while a film is playing. However, this isn’t really a photo of a movie, as much as it is just a photo of a photo: an image of one of the many thousands of frames which together make up an entire movie. You could instead try pointing it at spools of celluloid film as an attempt to represent the material base of a movie; though, we don’t really watch the physical filmstrips as much as the light which passes through them. Perhaps movies are not tangible objects as much as they are a tradition or activity, so maybe it would be more accurate to photograph an auditorium of spectators all collectively gazing at the same screen. Yet most movie-watching nowadays is not a collective activity but a solitary one, taking place in living rooms rather than theatres.

“What is cinema?” is a question which has plagued the medium since its very beginning. Is it more like photography or like theatre? Is it the filmstrip or its exhibition? Is it an art form or a technology? The advent of sound in the 30s radically altered what cinema was understood to be (and what audiences expected from it), as did the invention of television in the 50s and 60s, which lifted the moving-image away from the theatre and into people’s homes via new broadcasting technology. At least back then cinema still had its material base—the materiality of the celluloid filmstrip—to differentiate it from other mediums. This, of course, was upended in the 90s with the proliferation of digital cameras, and over the next fifteen years cinemas began replacing their film projectors with digital ones. Now watching a film in its original analog format, the way it was conventionally consumed for the first century of its existence, is an experience relegated to special events at one of the few cinemas which still have 35mm or 70mm projectors, or showings at art galleries for cinephiles. Streaming movies online is now the most dominant form of spectatorship, and the materiality of celluloid has been overtaken by the electromagnetic transmission of ones and zeros. If one thing has remained consistent over the 100+ years of the medium, it is that cinema has been in a permanent state of identity crisis.

So then, with all of this in mind, how do you take a photo of an entire movie?

Let’s look at two ways that artists have gone about answering this very question (to opposing ends). The first example speaks to the value of film as an analog medium, while the latter highlights the logics at play when cinema goes digital.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

In 1976, New York-based Japanese-born photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto had a hallucinatory vision: “My internal question-and-answer session leading up to this vision went something like this: ‘Suppose you shoot a whole movie in a single frame?’ The answer: ‘You get a shining screen.’” This epiphany led to his Theaters series, which began with U.A. Playhouse, New York (1978), and includes more than a dozen long-exposure photos of picture houses and drive-ins across America and Japan over a 27-year period.

The photographs are made like this: when the movie begins in the evacuated theatre, he opens his camera’s shutter, and when the movie finishes, he closes it. The result is an eerie long-exposure image where all of the film’s individual frames blur into a singular, homogenous glow.

Sugimoto remarks: “to watch a two-hour movie is simply to look at 172,800 afterimages. I wanted to photograph a movie, with all of its appearance of life and motion, in order to stop it again.”

The glow also illuminates the auditorium, drawing our eyes to the baroque art deco interiors which surround the screen. The central white screen, which is the result of perpetual movement, counterposes the stasis of the theatre. The whiteness indexes continual change and motion, while the darkness signals what stays the same.

The aesthetic of Sugimoto’s imagery is one which is distinctly analog. Not just because it is shot on an analog medium or is depicting one—both of which are true—but because it also appears to enact what the analog actually is. In his book Laruelle: Against the Digital, Alexander Galloway explores the contrasting nature of the digital and the analog. He describes the digital as the splitting of one into two (demarcation and discretisation) and the analog as merging of two into one (integration, consolidation, and totality). Sugimoto’s photographs clearly sit on the side of the latter, converging all of the disparate wavelengths of light from each frame into a formless, undifferentiated singularity.

The screen becomes a site of limitless potentiality. In capturing the entirety of a film within a single frame, he inadvertently captures every single film that exists or could ever exist, since under these conditions every movie looks the same. The homogenous white glow comes to represent the innumerable permutations of colour and movement that the cinema’s screen can sculpt within the confines of its frames.

Compressing a movie removes all the specifics and elucidates its essence: light. This underlying luminosity is described by Sugimoto in almost spiritual terms: “The light created by an excess of 170,000 exposures would be the embodiment or manifestation of something awe-inspiring and divine.”

Movie barcodes

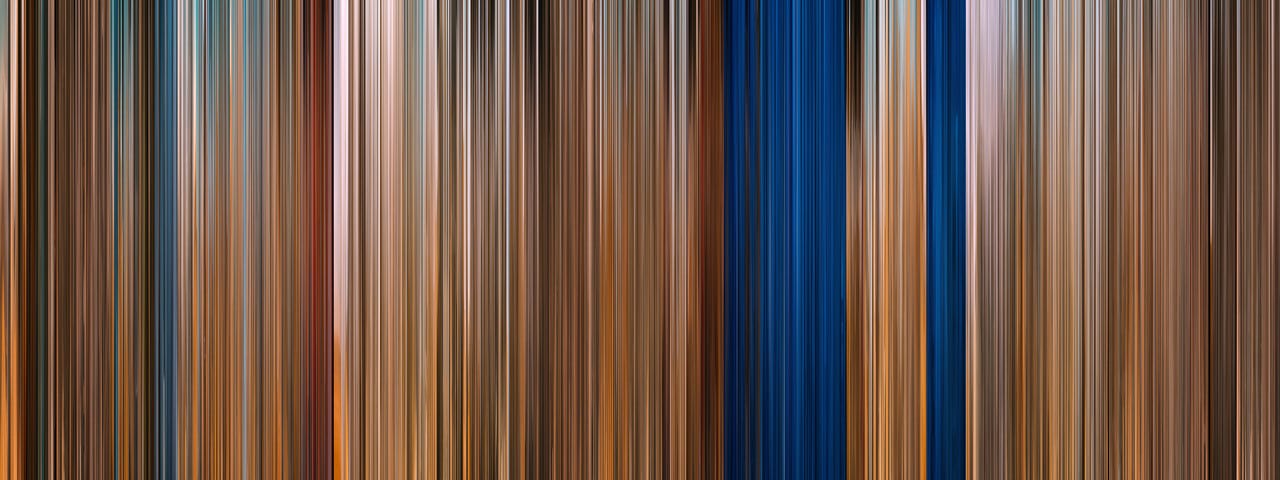

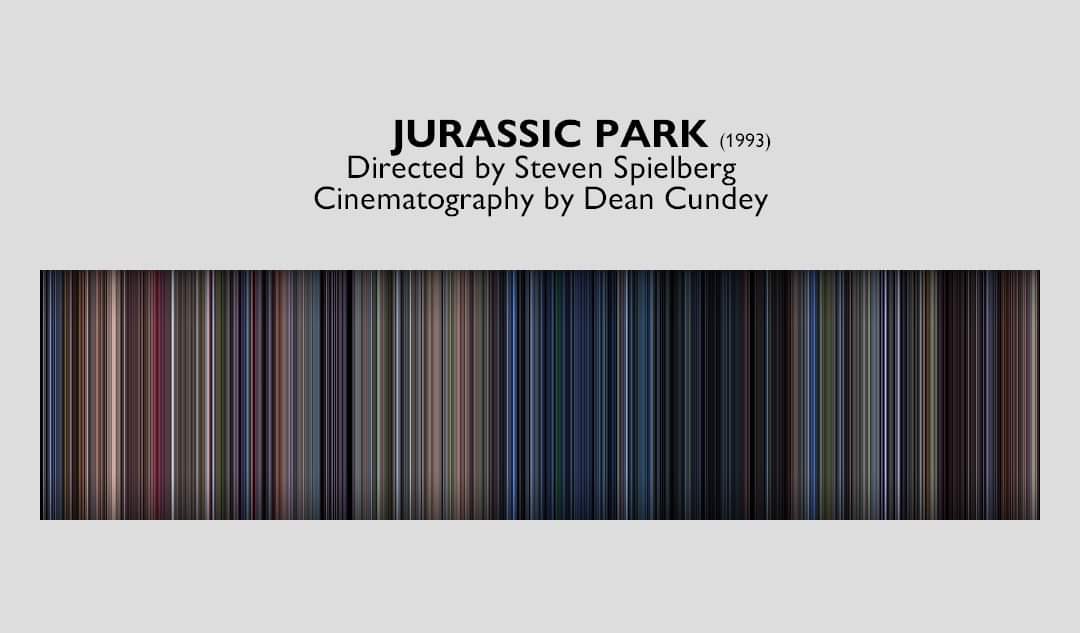

Thirty years after Sugimoto’s first theatre photos, the emergence of so-called “movie barcodes” have taken an entirely different approach to answering the question “how do you take a photo of movie?” Unlike Sugimoto’s singular vision, movie barcodes are crowdsourced and plentiful, sold as posters on sites like moviepalette.com or many an Etsy store. There are a number of Instagram and Tumblr accounts dedicated to these types of images, as well as sites which will let you generate your own for free. In movie barcodes, each frame of a film is compressed into a one-pixel-wide column and arranged chronologically from left to right. There are many different techniques for creating these “barcodes.” Some take the average colour of every frame, others determine the dominant colour, while some try to preserve all the colours of a given frame within its pixel wide strip, each process giving differing results.

While the images are undoubtedly fascinating, potentiality offering insights about a film’s colour palette or how a movie’s aesthetic changes over its duration, it is hard to not feel ambivalent about what their automated production is symptomatic of.

“If film-as-light is the precondition for Sugimoto’s entrancing theatre photos, then for these movie barcodes it is film-as-data: numbers, algorithms, computation.”

In digital photography, light which hits the camera’s sensor is translated and disassembled into a string of numbers which can then by reassembled and turned back into light once the file is reopened and displayed on a screen. This logic of algorithmic disassembly and reassembly is central to digital imagery. A file is just instructions on how to configure an array of pixels to re/create a specific image. An image file is not the image itself, but more like its recipe.

If film-as-light is the precondition for Sugimoto’s entrancing theatre photos, then for these movie barcodes it is film-as-data: numbers, algorithms, computation. These images are not possible without the movies first existing as arrays of digits which reflect the colour and luminosity of each pixel. By aggregating, averaging and sorting these numerical values which make up the film’s frames, movie barcodes are a kind of data visualisation, just like graphs, pie-charts, diagrams, and so on. Consciously or not, they reflect the aesthetic of Big Data.

The conclusions the two images come to are diametrically opposed. With Sugimoto’s photographs, the film being shown is irrelevant. The pictures expose a more fundamental essence—or spirit—which binds all of cinema together. On the other hand, the movie barcodes create a distinct fingerprint of each movie. Purely informatic, endlessly differentiable. Now, a movie is just a digital file which can be viewed and processed in a variety of different ways: watched 24-frames-per-second or presented entirely as a barcode—both are equally as valid. Perhaps digital cinema is itself already a form of data visualisation, unavoidably statistical in nature.

While not inherently problematic, it is interesting how the emergence of these images—circa 2011—coincide with the rise of streaming on platforms like Netflix as the dominant mode of movie consumption. It only makes too much sense. Even the term movie barcode makes reference to our current regime of logistical, informatic capitalism where the ubiquity of barcodes works to connect physical commodities to their digital counterparts. While items are scanned in the physical world, often to retrieve information such as their price, their positions on lists, catalogues, and databases are continually updated in the digital realm. What does it mean that cinema is now delivered to us the same way that Amazon coordinates its warehouses, or through the same networked infrastructures that mediate drone strikes and government surveillance?

Contemporary theory has long pitted the analog against the digital (see Brian Massumi’s “On the Superiority of the Analog” and, more recently, Alexander Galloway’s article “Golden Age of Analog” or his book Laruelle: Against the Digital), a battle which has been revitalised in the past few years. The popular re-emergence of vinyls, cassettes, disposable cameras, etc. are certainly in part to thank. Though, for media theorists, the concern is less about the aesthetic superiority/inferiority of the analog/digital (as is the case with the celluloid fetishism of Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan and Paul Thomas Anderson). It’s not about the superficial beauty of film grain or the unique timbre of a record, but rather what the digital actually enacts. The digital ruptures and splits; it creates dualisms and binaries. The digital is not something which emerged with computers, but a technique of splitting which has existed long before the digital camera (the alphabet is a digital technology insofar as it made up of discrete integers: a, b, c, and so on). Even movies presented on film are not without digitality: filmstrips, after all, are demarcated into discrete frames which make up the illusion of movement.

While taking a photo of a movie may be a fool’s errand, different attempts—more so in the ways that they fail rather than succeed—probe at the unsolvable question: what is cinema?

“If film-as-light is the precondition for Sugimoto’s entrancing theatre photos, then for these movie barcodes it is film-as-data: numbers, algorithms, computation.” Obsessed with this!